The Pluriversal Politics of Radical Publishing's Scaling Small

Friday, October 18, 2024 at 10:22AM

Friday, October 18, 2024 at 10:22AM Enjoying the Publishing After Progress special issue of Culture Machine, edited Rebekka Kiesewetter, now that it’s online.

I've been re-reading Femke Snelting and Eva Weinmayr’s ‘Committing to Decolonial Feminist Practices of Reuse’. I particularly like the suggestion Snelting and Weinmayr make regarding the Non-White-Heterosexual-Male License: ‘What if this licence would have pushed its point even more clearly, suggesting, for example, that privileged reusers should not use their natural name for attribution, or remove any credits altogether?’

I've also been re-reading Jefferson Pooley's 'Before Progress: On the Power of Utopian Thinking for Open Access Publishing’. In the following comments on 'Before Progress' I'll only speak to some of the radical open access publishing projects I'm most closely associated with: Culture Machine, Open Humanities Press, Radical Open Access Collective, COPIM ... But my experience of these projects is that, to recast Pooley’s words, scaling small does believe a ‘viable alternative’ system to the extractivism of the for-profit oligopolists is possible (contrary to Richard Poynder's impression of it), and so does have an aspect of utopianism.

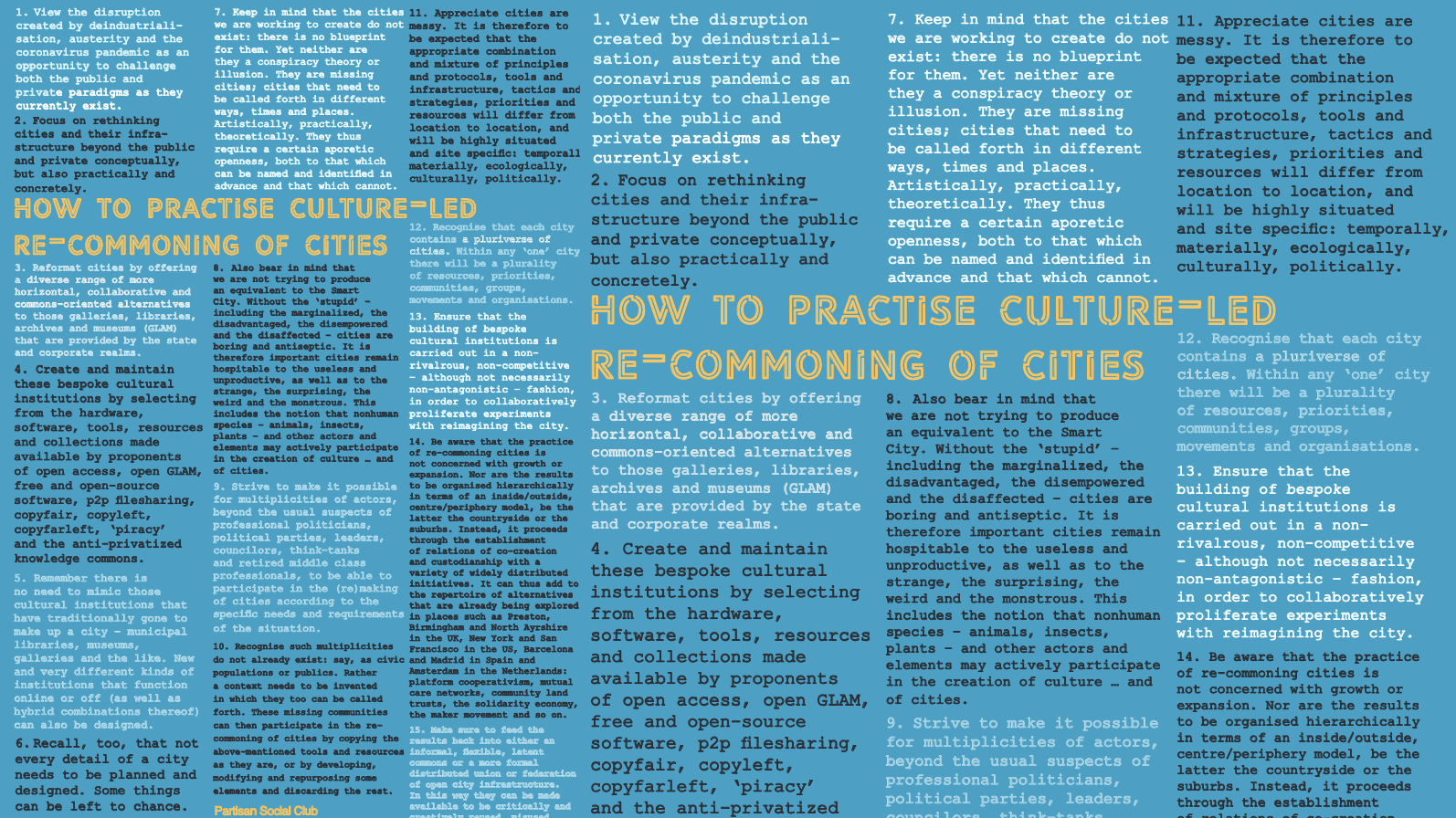

The scaling small element of these radical publishing projects, being an ethico-political stance, is not indicative of a retreat from such a progressive political vision of something better: it is the political vision. It's just that the emphasis on diversity means the politics of scaling small is better understood less in terms of universalism and perhaps more in terms of something like, say, pluriveralism, in the sense of the anticapitalist, antiracist, antiheteropatriarchal politics of certain Latin American activists and theorists.

Scaling small is thus very much concerned with enacting – and even telling a utopian story about – a shift toward a diverse, commons-based and postcapitalist (and, contra Poynder again, non-niche) way of living, working and thinking that is concerned with the principles of degrowth and postextractivism, not least as a way of addressing the environmental devastation caused by late capitalist society’s consumer culture.

I also wonder if what I'm characterising as the (more pluriversal) politics of scaling small is not so very far away from Erik Olin Wrights' own utopian politics, as referred to approvingly by Pooley. If so, then for me this is perhaps better illustrated by a book of his Pooley doesn’t have space to mention in 'Before Progress'.

In How to Be an Anti-Capitalist in the 21st Century, Wright argues that political change requires a combination of at least four strategic logics:

1) Resisting Capitalism

We need some actors to build reimagined trade unions and social movements (such as the radical publishing movement?) capable of eroding neoliberalism by resisting the constant surveillance, performance monitoring and behavioural control that’s being normalised by Silicon Valley and its platform capitalist, gig economy and now AI-as-a-service companies. (The latter is what many of the large, profit-maximising, academic-publisher-turned-data-analytics-businesses are surely also in the process of becoming.)

2) Escaping Capitalism

We need others to experiment with means of escaping neoliberalism: through ‘community activism anchored in the social and solidarity economy’ (Wright), such as those campaigning to abolish the police or those self-organising groups that responded to the pandemic by plugging the gaps in care left by the market and state; and through the development of a range of cooperative, collaborative and commons-oriented initiatives of the kind associated with the radical open access publishing community.

But we also need some actors to go through the traditional democratic channels of political parties and government legislation:

3) Taming Capitalism

We need them to do so in order to tame the excesses of neoliberalism: by restoring to gig economy and other precarious workers the rights to sick pay and maternity leave they have lost; or by establishing new twenty-first century institutions such as the ‘data trust for digital workers’ proposed by economist Francesca Bria.

4) Dismantling Capitalism

We also need them to do so with a view to dismantling neoliberalism and helping transition 21st century society into something more socially, epistemologically and cognitively just. This could involve lobbying for the overwhelming dominance of Elsevier, Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor & Francis et al. to be brought to an end, and for scholar-led communities (including, say, the likes of the Radical Open Access Collective and ScholarLed) to be able to generate, capture, control, store, publish and share their own research, information and data on a self-managed social and ecological basis.

Still, Pooley may be right about a certain kind of exhaustion in the radical open access world. If he is, I agree it’s not the Richard Poynder/Peter Murray-Rust version, where lobbying government and funders only leads to open access being co-opted by neoliberalism, but taking an alternative route is too niche, offering little hope of systematic change. So the solution becomes giving up and waiting for the end of capitalism - which is less likely, or, as we know from Fredric Jameson/Slavoj Žižek/Mark Fisher, at least harder to imagine, than the end of the world.

I suspect it’s more akin to the kind of wearyness that, in Doppelgänger, Naomi Klein attributes to Greta Thunberg. Klein suggests that Thunberg ‘no longer believes in that theory of change’ where delivering a speech to centrist political leaders about the climate crisis, the green economy and achieving net zero by 2050 will lead to meaningful action on their part. Thunberg, like many of us, has come to ‘the realization that no one is coming to save us but us, and whatever action we can leverage through our cooperation, organization and solidarities.’ Instead, Thunberg has found a way of ‘saving her words for spaces where they still might matter’, where they can be aligned with ‘principles and actions’, where people are not merely saying the right things (in the case of OA, say, about books having to be open access in the UK’s next REF?), and making promises with little or no intention of following through on them.

(The above was initially written as a Mastodon thread: @garyhall@hcommons.social. Jeff Pooley's response to it can be found on his blog here and on Mastodon here.)

Gary Hall | Comments Off |

Gary Hall | Comments Off |