‘The Most Spoiled Generation’: Boomer Theory, Algorithmic Hustle and the Drive Toward Something Else

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 at 9:36AM

Tuesday, February 10, 2026 at 9:36AM Response to Roger Malina, ‘Camel AI-Dung and Caravanserai and Gary Hall as a Camel Driver’.

First version presented at SCREENSHOT BABEL, a workshop run with Ester Freider as part of The Cyberbaroque: A Neologism-Based Symposium, November 20, 2025.

Updated for my Media Gifts blog December 2, 2025: http://garyhall.squarespace.com/journal/2025/12/2/the-independent-intellectual-vs-posting-zero-and-the-dead-in.html

Updated here February 10 for Roger F. Malina and Aperio AI

---

Albert Einstein is (falsely) reputed to have said: ‘Creativity is intelligence having fun’. Today, we might update that line to: ‘Creativity is human and machine intelligences having fun together’.

That small shift already places us in the terrain mapped by my colleague Roger Malina’s COLNLI Camel. It frames creativity not as a property of sovereign human genius, nor as a technical capacity of machines, but as something emergent from heterogenous assemblages: human and nonhuman, institutional and infrastructural, as well as often-invisible forces of energy and matter such as ‘sea, tide and storm’.

So, rather than accept Malina’s generous invitation to rebut ‘Camel AI-Dung and Caravanserai and Gary Hall as a Camel Driver’ – and the fun it has engaging with my new book Defund Culture (and the earlier Pirate Philosophy) – I want to continue to make trouble by proposing something different. Not a refutation so much as a change of route or direction: toward Malina’s COLNLI (collaboration of local and non-local intelligences) Camel itself, and what it invites us to think and ask.

I was particularly struck by the insistence in Roger Malina’s mischievous – and, importantly, unfinished – text that, as a ‘metaphor that can hold structure, movement, imbalance, humor, and adaptation at once’, the ‘COLNLI Camel is not an illustration of a problem. It is a practice of thinking. It invites different questions.’ It is this invitation I want to take up, especially as it bears on questions of generation, institutional hierarchies and ‘elite prestige economies’, and the place of theory and AI within them.

In a context in which ‘societies are undergoing a deeper reconfiguration of how memory, stability, ambition, and interpretation are distributed across human generations’, three challenges stand out:

- ‘How do we help younger generations lift their gaze without denying the complexity beneath their feet.’

- ‘The camel’s head is human, young, and angled downward. This represents younger generations whose ambition is real but whose visibility and footing are constrained…. Their challenge is not a lack of desire to participate, but the difficulty of seeing themselves reflected in institutions and futures dominated by older temporal rhythms.’

- The demographic shifts of our time are not a crisis to be managed but a structural condition to be understood…’

These issues cut close to why I’ve spent much of my working life in universities (although I’m not sure I’ve always experienced them as welcoming or supportive places, or ones that made me feel especially good. Clearly, I still need to digest this experience. After all, I’m a Makem who writes and publishes radical theory, what did I expect?)

Part of the point of universities, at least historically, has been to ‘provide spaces where society’s accepted, taken-for-granted collective beliefs can be examined, interrogated and put to the test’, as I put it in Defund Culture. Within the university, one space in particular has taken on the work of questioning the common sense, the customary, the familiar, the habitualised, the automatic, the well-known, the masked: this is theory. For me, however, theory is not simply a body of ideas housed within institutions. It’s also a set of practices concerned with reading, writing, publishing, licensing, copying, pirating and circulating ideas differently. As such, it focuses on infrastructures as well as content: copyright regimes, authorship protocols, funding models, and the ‘saddles’ that distribute weight unevenly across generations, demographics and intelligences. (As we know from Malina, a badly designed saddle doesn’t just make the ride uncomfortable; it injures those least able to absorb the strain.)

This role – of both the university and theory – remains crucial, even as the institution faces mounting pressure to abandon it. Attacks come from many directions: from Trump and his acolytes targeting Harvard and Columbia; from authoritarian culture-war warriors; from neoliberal insistence that higher education serve primarily an instrumental economic function, creating jobs, generating wealth; from funding regimes that punish anything that does not look like it will deliver outputs already known in advance; and from the slow hollowing out of the humanities. (See here and here for two accounts from just the other week of the pressures facing the humanities in the UK and US respectively.)

Yet for many members of the younger generations Malina mentions, much of that which is produced under the guise of ‘theory’ no longer feels all that interesting or exciting. As far as they are concerned, what’s come to be dubbed boomer theory has produced the same critique of capitalism and its institutions over and over again, with only minor variations. In the words of post-internet ‘star’ artist and theorist Joshua Citarella:

This is a theory of media and culture that was largely propagated by tenured professors who grew up during the postwar boom. All they want to do is talk about dismantling corrupt institutions and whatever, whatever it is that they’re getting up to – the most spoiled generation in the history of the world. This is just not scaling to the lived experience of millennials and Zoomers, who now have a different set of values.

Citarella describes a situation in which young people would work in universities, ‘and they would learn to reproduce the language and affect of people who had high-status positions, they may or may not believe those things, and their peers may or may not believe those things…. this is a bad sign for the life cycle of an institution – when young people who participate in it merely espouse the values to advance their careers, but they do not meaningfully believe them.’

And that’s assuming young people would want to work in universities at all. For many today, the academy appears unavailable, unattractive, precarious, conservative, hypercompetitive, elitist even, the province of an aging demographic indeed.

(The artist Cem A. recently identified a similar consensus as having formed in the art world, albeit with less emphasis on generational factors. There, what he calls:

Consensus Aesthetics blocks the possibility of a discussion with real consequences and avoids contradiction, because genuine criticism carries political cost and any tension generates bad optics. Institutions that toe this lowest common denominator thematic line don’t confront the present; they perform around it, with familiar acts that are becoming harder to digest as if curated in a parallel timeline where the current crises never occurred. Without engaging with complexity or facing contradiction, politics slides into branding and art into a loop of moral cues: care, solidarity, decolonisation, ecology, crisis.)

So, the question becomes one I’m very much concerned with at the moment: where else might the practice of theory – and its questioning of what is otherwise accepted as commonsense – take place for young people?

One answer is the figure of the theorist-as-content-creator, who sustains their practice by building an audience through social media (including LinkedIn), subscription platforms (e.g. Substack and Patreon), and even the sale of merchandise. Here, influence replaces citation and metrics replace peer review. The appeal is understandable. By-passing the traditional liberal gatekeepers of the ‘old elite’ – universities, academic presses, peer-reviewed journals – and instead using digital channels – YouTube, newsletters, podcasts, Instagram – to present oneself as an independent and self-organised writer and researcher can feel like a refusal of inherited institutional hierarchies.

With regard to Citarella specifically, a post on LinkedIn by Sylvain Levy captures the shift well:

Citarella has intuited something essential: that today's artist is not only a creator of objects, but also a designer of attention systems. His cultivated persona – muscular yet reflective, ironic yet sincere – is not vanity, but media literacy. Influence is now a material. Brand is now a tool. Audience feedback is a form of co-authorship. The post-digital artist is both author and avatar. For collectors, and institutions, there is a deeper lesson. The arena has changed. Platforms are the new museums, discourse is the new exhibition, and audiences no longer arrive as mere spectators, but as participants in an ideological economy that moves at the speed of memes. To remain relevant, art must inhabit these spaces intelligently, not dismissively. It must accept that a Twitch stream can be more culturally significant than a white cube and that a podcast can achieve what press releases cannot.

But here the camel stumbles.

For one thing, this model requires privilege: financial, social, cultural. It is far easier for white, middle-class, well-educated men with existing visibility to survive as a self-branded micro-enterprise. This is not a pathway to independence that can be followed by everyone.

For another, even when such practices are animated by ‘post-individualist’ values – community, collaboration, connectivity – the power of the platforms is not so easy to escape. Too often, practitioners fall back into the neoliberal subjectivity of the commodified ‘authentic’ self that is associated with late capitalist grifter culture.

Morgane Billuart spells this out precisely: the critical intellectual becomes the product, knowingly if reluctantly, because self-branding works. It builds audiences. It generates income. But it also demands constant output – feeding the algorithms, chasing relevance – at the cost of exhaustion, anxiety and burnout. Progressive influencer Hasan Piker reportedly broadcasts 7 hours a day on his Twitch stream, every day except Sundays; he estimates he spent 42% of 2020 alone livestreaming.

So how much of an alternative is this really? Is turning oneself into a monetisable persona a survival strategy in the face of institutional and state funding cuts? Is it the price of doing interesting critical and creative work today? Or is it just another modality of control, one that is different in form, but not in logic, from that of the university and old elite?

As I’ve said before, my suspicion is that, for reasons of tactics and strategy, it’s both at the same time. (More entanglement than opposition, here, too.)

Given each of these models has its problems, perhaps what’s needed is neither form of control – neither the legacy theorist of print books and peer-reviewed journals, nor the online intellectual-come-influencer of Instagram and Substack – but something else besides?

Which brings us back to the COLNLI Camel and the CaravanserAI.

What Roger Malina’s camel – which is neither a symbol of domination nor subservience – offers is not a choice between the prestige economy of inherited institutions and the algorithmic hustle of the platform economy. Instead of ‘collapsing into hierarchy or competition’, it proposes a practice of thinking about redistribution, reuse and reconfiguration: about redesigning the saddle (the infrastructure, norms, cultural narratives and institutional rules) rather than blaming the riders (or exhorting them with a PhD); about metabolising accumulated memory rather than being governed by it, or indeed drowning in AI shit formed on the ‘ground conditions’ of ‘climate, bodily fragility, planetary time, and energetic limits’.

This ‘landscape under exploration’, as Malina calls COLNLI land, is where my multi-generational collaborators and I situate much of our work. With our caravans we are trying to avoid simply acting as legacy ‘liberal’ theorists; while also resisting the dominant contemporary alterative: the critical writer and researcher as self-organised entrepreneur. Instead, we’re experimenting with the invention of that something else besides: in our case forms of collective, commons-oriented and radically relational intellectual and cultural practice that aren’t shaped by the need to impress a university press or brand ourselves into exhaustion.

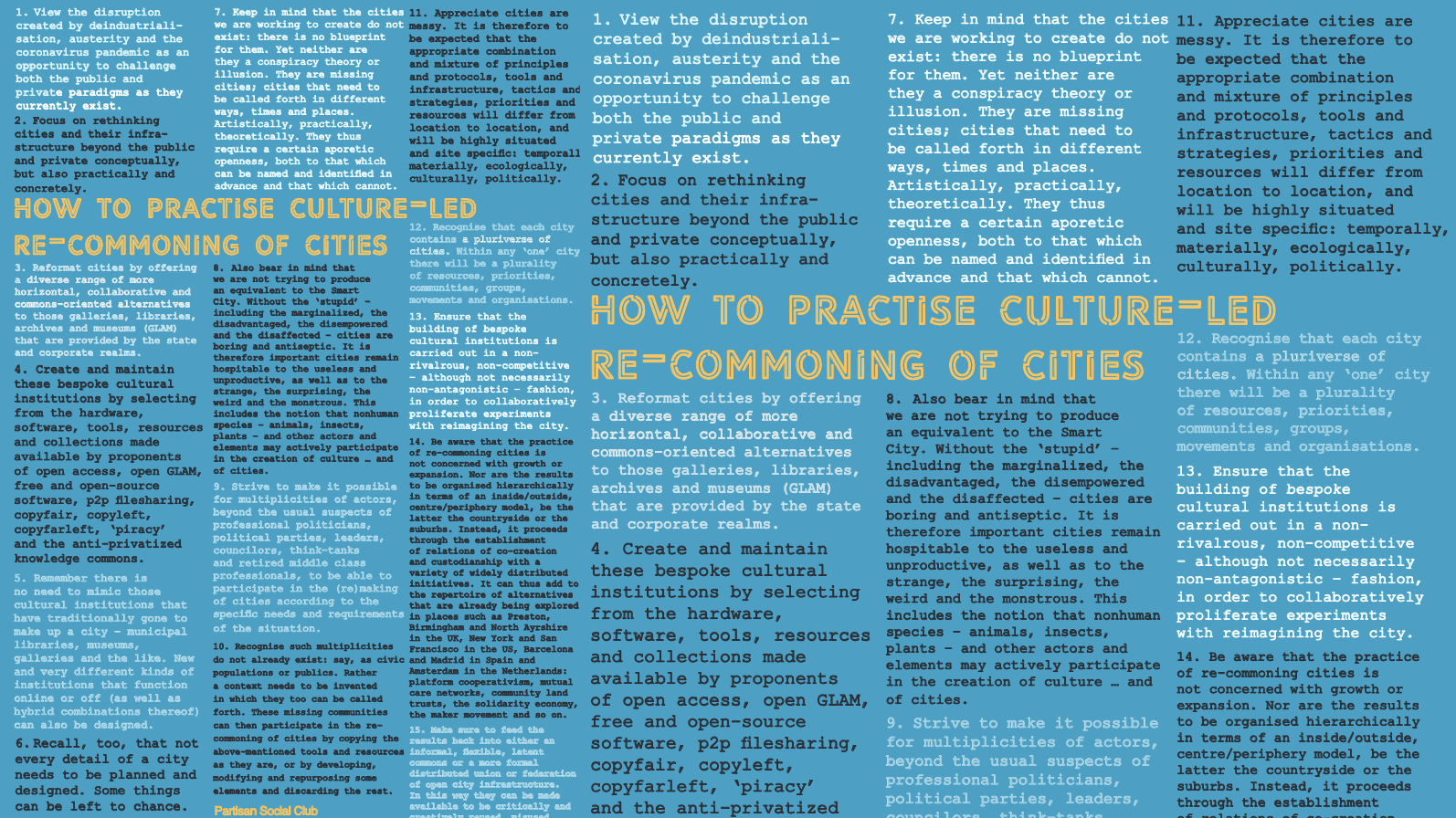

Culturally, such models are not so difficult to develop and stress test. Economically, they’re far harder – especially if we want to avoid slipping back into what is neoliberal entrepreneurialism by another name. That is why Defund Culture insists on redistributing opportunities and resources, time and attention, including across ages, demographics and intelligences, local and non-local; on ‘changing who controls the oases’; on building caravanserai – which historically were not destinations but stopping places containing the infrastructures of hospitality, exchange and repair – rather than new brands.

From this perspective, AI matters less as a tool or (weather) system of stored data and memory than as a provocation. It forces us to ask different questions; questions we should have been asking anyway, but haven’t, because the power and authority of capitalism, liberalism, humanism and the university have rendered them habitual and invisible. What is authorship? What counts as intelligence, cognition, originality? Whose work gets to travel? Whose labour is recognised? Who (or what) gets to create, and under which conditions? What kinds of lives and practices are made possible by our organisations and institutions; and which do they foreclose? Who owns the oases? Who sets the routes? Who gets exhausted or left behind? What gets excreted along the way?

AI exposes how customary our ideas have become. In doing so, it opens the possibility of imagining unanticipated and unexpected ways of thinking and living – ones that are full of potential in that they do not simply reproduce white, male and middle-class norms under the guise of either academic prestige or platform visibility, so our caravans don’t ‘keep circling back to the same gated stops’.

Whether we can rise to that opportunity remains an open question.

I’ll leave it to others to judge how creative, intelligent or fun this change of route has been. But if the COLNLI Camel Caravanserai teaches anything, it’s that the future – even if it involves a long journey across uneven ground – can be approached together, through careful practices of coexistence, collaboration and ethical digestion.

Camel shit-come-fuel, soil, building material, commons and all.

Gary Hall | Comments Off |

Gary Hall | Comments Off |