Recent open-access publications by Gary Hall and by editors Hanna Hölling, Aga Wielocha, and Josephine Ellis offer two distinct yet complementary interventions into contemporary debates about culture, institutions, and inequality. Read together, Defund Culture: A Radical Proposal and Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation help articulate a broader narrative about how culture is funded, transmitted, neutralized, and—potentially—reanimated.

While Hall advances an abolitionist critique of cultural funding regimes, Activating Fluxus explores how historically anti-institutional practices can persist, mutate, and remain alive within and against institutional frameworks. The tension between these positions is not a weakness; it is precisely where the most productive questions emerge.

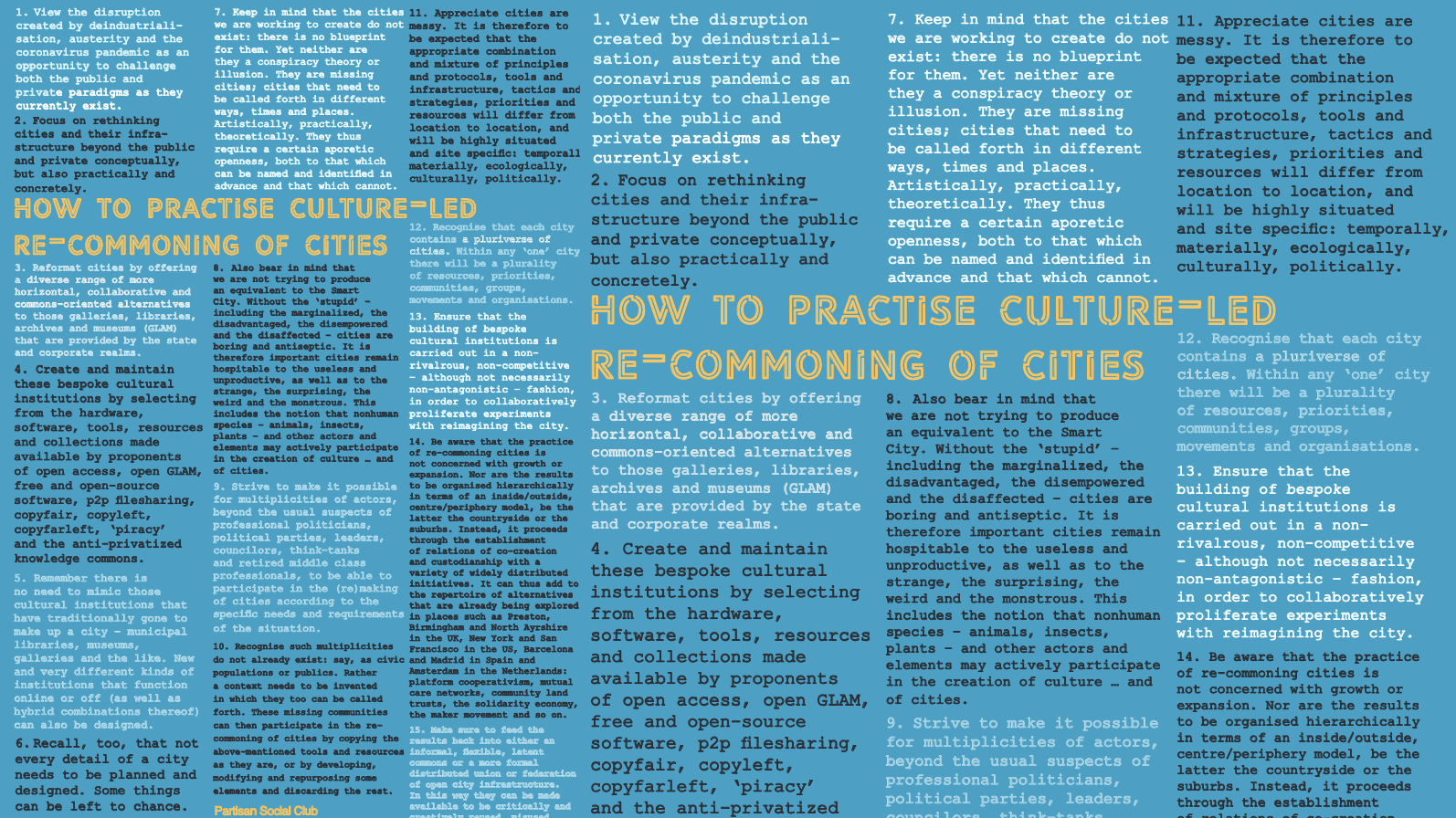

Defund Culture: Withdrawal as Structural Critique

At the heart of Defund Culture is a refusal to accept the existing cultural landscape as neutral or inevitable. Hall challenges calls to “support the arts” that fail to interrogate which cultures are supported, through which institutions, and for whose benefit.

The book argues that the persistent dominance of white, male, and middle-class voices in the arts, media, and academy is not an accident of representation but the outcome of longstanding funding arrangements, institutional hierarchies, and prestige economies. Within this framework, diversity initiatives and access programs often function as legitimation mechanisms rather than engines of transformation.

Hall’s provocation is abolitionist in spirit. Rather than reforming institutions from within, he asks what it would mean to disinvest from cultural systems as they currently operate, redistributing resources away from elite organizations and toward commons-oriented, collective, and radically relational alternatives. Importantly, this is not a call for “less culture,” but for a reconfiguration of cultural value, authority, and care.

Fluxus as a Counter-History of Cultural Survival

Activating Fluxus, Expanding Conservation enters the conversation from a different angle. Rather than beginning with funding structures, it takes Fluxus—a movement defined by ephemerality, participation, and resistance to commodification—as a stress test for cultural institutions.

Fluxus challenged the idea that artworks should endure as stable objects. Scores, events, instructions, and collective actions replaced singular artifacts. The central problem addressed by Activating Fluxus is therefore not how to preserve objects, but how to care for practices that were never meant to be fixed.

The book proposes “activation” as an expanded model of conservation: conservation as interpretation, reenactment, transmission, and care. In this view, meaning is not stabilized but continually renegotiated among artists, conservators, curators, and participants. Conservation becomes a generative, decolonial, and epistemically distributed practice, rather than a technical or custodial one.

Redistribution of Authority, Not Just Resources

One of the most significant contributions of Activating Fluxus is its implicit argument that conservation redistributes epistemic authority. Expertise is no longer centralized in institutions alone; it is shared across communities, performers, scholars, and caretakers. This move closely parallels Hall’s call for epistemic pluriversality, even as it operates within existing institutional contexts.

Where Defund Culture focuses on withdrawing legitimacy and funding from elite systems, Activating Fluxus demonstrates how authority can be redistributed through practices of care, interpretation, and participation. These are different levers acting on the same structural problem.

A Productive Tension: Abolition and Transformation

The two books diverge most clearly on the question of institutional possibility.

Hall is skeptical that dominant cultural institutions can truly surrender their hierarchies, prestige mechanisms, and extractive logics. From this perspective, reform risks becoming a way of prolonging institutional life without altering its foundations.

By contrast, Activating Fluxus suggests that some institutions can be forced to mutate—to accept instability, incompleteness, and shared authority—if they wish to engage meaningfully with practices like Fluxus. The book does not deny institutional power, but it explores how that power might be destabilized through new models of care and transmission.

Rather than choosing between these positions, it may be more productive to see them as addressing different phases of the same problem: dismantling cultural accumulation on the one hand, and inventing non-extractive afterlives for fragile practices on the other.

Open Access as Infrastructure, Not Afterthought

It is not incidental that both books appear as open-access publications. Hall’s work is released under the

CC4r (Collective Conditions for Re-Use) framework via

mediastudies.press, while

Activating Fluxus is made freely available by

Routledge.

In narrative terms, this matters. Defund Culture critiques the political economy of cultural accumulation, while Activating Fluxus demonstrates alternative circulatory logics already operating within legacy systems. Publishing models here are not neutral vessels; they are part of the argument.

Toward a Shared Narrative

Taken together, these two books suggest a broader trajectory:

-

Critique – Naming how cultural institutions reproduce inequality and exclusion.

-

Exemplars – Recognizing practices (like Fluxus) that resist objectification and commodification.

-

Transmission – Inventing ways to care for and relay such practices without domesticating them.

If Defund Culture asks what must be dismantled, Activating Fluxus asks how vulnerable, collective, anti-elite practices can persist once the mansion is refused. One pushes toward rupture; the other toward experimental continuity.

Together, they sharpen a central question for contemporary cultural work: not simply how to fund culture, but how culture lives on—who carries it, who cares for it, and under what conditions it remains alive rather than merely preserved.

Thursday, January 22, 2026 at 10:13AM

Thursday, January 22, 2026 at 10:13AM

Gary Hall | Comments Off |

Gary Hall | Comments Off |