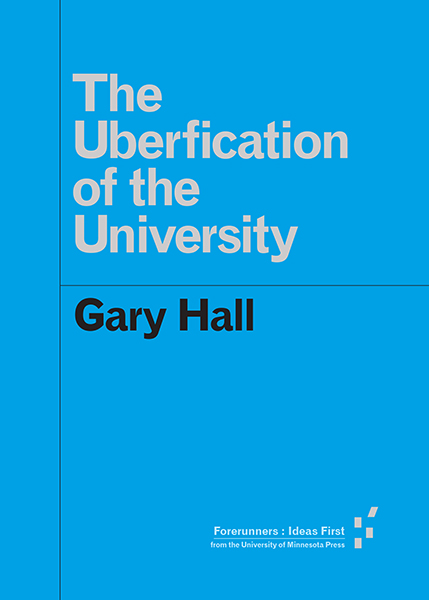

Interactive Version Of The Uberfication Of The University Now Available In Minnesota's Manifold Series

Sunday, April 9, 2017 at 6:00PM

Sunday, April 9, 2017 at 6:00PM Funded through the generous support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Manifold is a collaboration between University of Minnesota Press, the GC Digital Scholarship Lab at the Graduate Center, CUNY, and Cast Iron Coding.

Minnesota began work on the Manifold project two years ago, aiming to create a responsive platform for interactive books that would help university presses share long-form monographs through an appealing and elegant interface. On the Manifold site, there are a selection of projects from the University of Minnesota Press that may be read, annotated, highlighted, and shared through social media. Each project has a homepage that presents an overview of the text, provides a quick link to the text, aggregates recent activity, showcases the evolution of the project, and shares resources—images, videos, files, PDFs, image collections—that have been added to the text. Images that were part of the print version will appear in-line; resources that have been added for the Manifold edition will appear to the left of the text. Texts are responsive and may be read on any device, though the mobile versions are not yet fully featured.

Manifold is an open-source project. The code is available on Github. For a longer introduction to the project, please read 'Building Manifold', by Project Co-PIs Doug Armato and Matthew K. Gold. To learn more about the technology behind the platform, please read 'A Technical Introduction to Manifold' by Manifold Lead Developer Zach Davis.

(For the full version of the above text, please read 'Manifold Beta Now Available'.)

Ten Ways To Affirmatively Disrupt Platform Capitalism And The Sharing Economy Of Uber And Airbnb ♯3: Become a Microdatapreneur

Tuesday, February 21, 2017 at 2:53PM

Tuesday, February 21, 2017 at 2:53PM (This is part of a series of posts in which I provide ten proposals as to how to affirmatively disrupt platform capitalism and the corporate sharing economy of Uber, Airbnb et al. Together these posts constitute the draft of a text provisionally titled Data Commonism vs Übercapitalism designed to follow on from my recently published short book, The Uberfication of the University. If the latter provides a dystopian sense of what is lying in store for many us over the course of the next few years, Data Commonism vs Übercapitalism is more optimistic in that it shows what we can do about it.

The first text in this series, Data Commonism: Introduction is here.

The Uberfication of the University is available from Minnesota University Press here. An open access version is available here.)

We Don’t Have To Live Like This: How To Affirmatively Disrupt the Disrupters

A still further way we can endeavor to affirmatively disrupt the platform capitalists of the sharing economy is by working toward the kind of “universal micropayment system” Jaron Lanier envisages in Who Owns The Future: “If observation of you yields data that makes it easier for… a political campaign to target voters with its message, then you ought to be owed money for the use of that valuable data.” In this system we would be paid for the data we generate if it turns out to be valuable. Our relationship with the platforms of the for-profit sharing economy would thus take the form of a “two-way” financial transaction in which we all “benefit, concretely, with real money,” rather than just a few San Francisco-based entrepreneurs and investors.

Interestingly, we do now have the means to apply a licence to specify how our data is to be protected and controlled and whether it can be shared. Project-if.com, for example, allows individuals to license their data: that produced using the Oyster travel card in London, say. As was made clear at the 2015 Big Bang Data exhibition at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, Project-if.com “let people decide whether their data is shared or not, who can access it, and what they can do with it... The prototype works on a blockchain, a transparent and secure data recording system.”

Such an approach has the potential to be disruptive of the for-profit sharing economy since it would allow us, if we so wish, to withhold our user data--data on which platform capitalist companies depend for their successful operation. One problem with Lanier’s idea, however, is that of scale. A universal micropayment system may result in some degree of financial redistribution. But while it provides a means of reuniting data with those users who produce it--in contrast to platform capitalist companies which work hard to keep the two apart--there is not really all that much we can do with our own small amounts of data. How much leverage would we have when it comes to negotiating a price for it, bearing in mind most of us will have to rely on these companies to determine for us the extent to which our data--including that we generate in our homes by using the Google Home voice assistant, or Amazon’s Echo, with its virtual PA Alexa--has actually contributed to a political campaign aimed at targeting voters, to stay with Lanier’s example?

Any money we succeed in obtaining in this fashion is likely to be relatively minor--along the lines of the royalty payment musicians receive from streaming services such as Spotify (between $0.006 and $0.0084 per play). Lanier’s universal micropayment idea therefore seems another approach that will do little to fundamentally alter the overall system of ubercapitalism.

(The same can be said of the musician Imogen Heap’s idea to change the music industry by using blockchain technology to ensure artists get paid. It is interesting how often blockchain technology is used to try to find a way for users to pay for everything in the form of micropayments. )

And what if the price we are offered is not acceptable? In reality, how much power are we likely to have to retain ownership and control of our data more broadly, compared to that of large, aggressive, for-profit corporations such as Google, Amazon, and Uber: especially if these corporations hold the view that, in the words of Carl Bildt, chair of the Commission on Internet Governance thinktank, “Barriers against the free flow of data are, in effect, barriers against trade.” As Dymtri Kleiner reminds us, “their business model depends fundamentally on surveillance and behavioural control.” So isn’t any attempt to adopt a protectionist stance with regard to our own data likely to be perceived as a direct attack on these companies on our part? (Either that or we’ll find ourselves identified as a potential threat by the national security surveillance systems of the NSA, GCHQ, et al.)

Moreover, for Clare Birchall, it is not at all “clear that data belongs to us in the first place in order for it then to be given or taken”--or monetized, in this case. Instead, “we are within a dynamic sharing assemblage: always already sharing data with human or non-human agents.” Birchall introduces the term “shareveillance” to describe the “condition of consuming shared data and producing data to be shared in ways that shape” what she refers to as an “an ascendant shareveillant subjectivity.” This is a “subject who is at once surveillant (veiller ‘to watch’ is from the Latin vigilare, from vigil, ‘watchful’) and surveilled. To phrase it with a slightly different emphasis: the subject of shareveillance is one who simultaneously works with data and on whom the data works.”

The main problem I have with Lanier’s idea for a universal micropayment system, though, is that it maintains us in the position of being ubercapitalist microentrepreneurs--not just of ourselves but of our data too.

The Philosophical Salon - new book from Open Humanities Press' Critical Climate Change series

Tuesday, January 24, 2017 at 11:02AM

Tuesday, January 24, 2017 at 11:02AM We're delighted to announce the latest release from the Critical Climate Change series: The Philosophical Salon, edited by Michael Marder and Patricia Vieira.

http://www.openhumanitiespress.org/books/titles/the-philosophical-salon/

Through the interpretative lens of today’s leading thinkers, The Philosophical Salon illuminates the persistent intellectual queries and the most disquieting concerns of our actuality. Across its three main divisions—Speculations, Reflections, and Interventions—the volume constructs a complex mirror, in which our age might be able to recognize itself with all its imperfections, shadowy spots, even threatening abysses and latent promises. On the cutting edge of philosophy, political and literary theory, and aesthetics, this book courageously tackles a wide array of topics, including climate change, the role of technology, reproductive rights, the problem of refugees, the task of the university, political extremism, embodiment, utopia, food ethics, and sexual identity. It is an enduring record of an ongoing conversation, as well as a building block for any attempt to make sense of our world’s multifaceted realities.

Through the interpretative lens of today’s leading thinkers, The Philosophical Salon illuminates the persistent intellectual queries and the most disquieting concerns of our actuality. Across its three main divisions—Speculations, Reflections, and Interventions—the volume constructs a complex mirror, in which our age might be able to recognize itself with all its imperfections, shadowy spots, even threatening abysses and latent promises. On the cutting edge of philosophy, political and literary theory, and aesthetics, this book courageously tackles a wide array of topics, including climate change, the role of technology, reproductive rights, the problem of refugees, the task of the university, political extremism, embodiment, utopia, food ethics, and sexual identity. It is an enduring record of an ongoing conversation, as well as a building block for any attempt to make sense of our world’s multifaceted realities.

Contributors: Robert Albritton, Linda Martín Alcoff, Claudia Baracchi, Geoffrey Bennington, Jay M. Bernstein, Costica Bradatan, Jill Casid, David Castillo, Antonio Cerella, Anna Charlton, Claire Colebrook, Sarah Conly, Nikita Dhawan, William Egginton, Roberto Esposito, Mihail Evans, Gary Francione, Luis Garagalza, Michael Gillespie, Michael Hauskeller, Ágnes Heller, Daniel Innerarity, Jacob Kiernan, Julia Kristeva, Daniel Kunitz, Susanna Lindberg, Jeff Love, Michael Marder, Todd May, Michael Meng, John Milbank, Warren Montag, T. M. Murray, Jean-Luc Nancy, Kelly Oliver, Adrian Pabst, Martha Patterson, Richard Polt, Gabriel Rockhill, Hasana Sharp, Doris Sommer, Gayatri Spivak, Kara Thompson, Patrícia Vieira, Slavoj Žižek.

Disrupting the Humanities: Towards Posthumanities - special issue of JEP

Monday, January 9, 2017 at 3:31PM

Monday, January 9, 2017 at 3:31PM We are pleased to announce the publication of a special issue of the Journal of Electronic Publishing: ‘Disrupting the Humanities: Towards Posthumanities’, edited by Janneke Adema and Gary Hall.

‘Disrupting the Humanities: Towards Posthumanities’ consists of a selection of video-articles by Johanna Drucker, Mark Amerika, Erin Manning, Monika Bakke, Endre Dányi, Lesley Gourlay, Silvio Lorusso, Niamh Moore, Karen Newman, SØren Pold, Craig Saper, Sarah Kember, and Iris van der Tuin.

It is available for free, open access, CC-BY, here:

http://www.journalofelectronicpublishing.org/

‘Posthumanities: The Dark Side of “The Dark Side of the Digital”’

Adema and Hall have written a 10,000 word opening essay, discussing the conceptual premises that underly this special issue. Engaging with various discourses around the digital humanities, the essay outlines the experimental mode in which the videos included in the issue have been edited, as well as pointing to the idea of "posthuman humanities".

Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0019.201

A table of contents for this special issue of the Journal of Electronic Publishing is provided below.

-----

Disrupting the Humanities: Towards Posthumanities

The Journal of Electronic Publishing (JEP)

Volume 19, No. 2 winter 2016

Edited by Janneke Adema and Gary Hall

Contents

1 Maria Bonn, A Note From JEP

2 Janneke Adema and Gary Hall, Posthumanities: The Dark Side of “The Dark Side of the Digital”

PART ONE – Creating Posthumanities: Disrupting Humanities Methodologies

Part one of Disrupting the Humanities consists of a radical exploration of new posthumanist methodologies that take into account the agency of technologies and other non-human actants involved in modern forms of knowledge production.

3 Monika Bakke, Deep Time Environments: Art And The Materiality Of Life Beyond The Human

4 Lesley Gourlay, Posthuman Texts: Nonhuman Actors, Mediators and Technologies of Inscription

5 Niamh Moore, “Humanist” Methods in a “More-than-Human” World

6 Iris van der Tuin, Reading Diffractive Reading: Where and When Does Diffraction Happen?

PART TWO – Performing Posthumanities: Disrupting Humanities Aesthetics

Part two looks at the ways in which research is mediated and performed. It focuses on a reconsideration of the aesthetics of scholarship, including the “aesthetics of bookishness.” In doing so it investigates the potential of more post-digital, hybrid and multimodal forms of knowledge creation.

7 Erin Manning, 10 Propositions for Research-Creation

8 SØren Pold, Ink After Print: Literary Interface Criticism

9 Johanna Drucker, Diagrammatic Form and Performative Materiality

10 Silvio Lorusso, The Post-Digital Publishing Archive: An Inventory of Speculative Strategies

PART THREE – Circulating Posthumanities: Disrupting Humanities Institutions

Part three of Disrupting the Humanities provides a critical examination of how research is disseminated and shared, be it by publication to peers or to students in a pedagogical setting, or by adopting practices of radical openness and experimentation to challenge the normative and often print-based (neo)liberal humanist assumptions of how scholars in the humanities communicate.

11 Sarah Kember, At Risk? The Humanities and the Future of Academic Publishing

12 Endre Dányi, Samizdat Lessons: Three Dimensions of the Politics of Self-Publishing

13 Craig Saper, Disrupting Scholarship

14 Mark Amerika, Glitch Ontology (A Video Performance)

15 Karen Newman, The West Midlands as an ‘Electronic Super Highway’: BOM and the Emergence of New Art Infrastructures